While I was still a computer science student at the University of British Columbia, I joined a young software startup called Robelle, named for the two founders Robert and Annabelle. I was the first employee.

As a requirement of my employment Bob and Annabelle insisted that I had to write my first technical paper, submit it to the 1980 International Hewlett-Packard General Systems User Group, and if accepted travel to the conference to present my paper.

That first paper, Checkstack & Controlling COBOL Stacks, was accepted. I had to ask permission of my UBC professors in fourth year to take a week off so that I could fly to San Jose, where I did my first ever professional presentation, at the tender age of twenty-two.

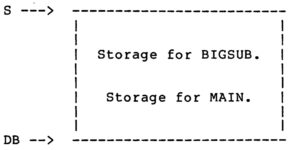

I remember how anxious I was before going on stage that first time, but I had no choice. My paper was in the proceedings and my time slot was booked. Here’s an image from that paper:

My only prior public speaking experience was when a previous employer had me take a weekend long public speaking course. In addition to forcing me to practice public speaking during that weekend workshop, the instructor taught me three important things that you should do in every presentation:

- Tell them what you are going to tell them.

- Tell them.

- Tell them what you told them.

Like most good advice, the principles are very, very simple. It is the practice of how you do this that is the challenge. I still follow these principles today, being as creative as I can be so that people are not obviously aware that this is the pattern of my presentations.

I think that we often do our best work when we don’t know what we are doing. Free of the shackles of previous experience we just go out and try things. Sometimes, we just repeat the mistakes of others. Other times, we strike out into a completely new area.

No one told me that 22-year olds are not supposed to go to international conventions and give presentations. At least in 1980 we weren’t supposed to. Today, it’s normal as the next generation of breakthrough technologies are often being invented by people much younger than I was then.

What does this have to do with leading others? I take away these powerful lessons:

- We should not assume someone young in age or role is incapable of taking on something new and ambitious.

- It is up to us to challenge those that follow us so that they have the opportunity to grow into what is next for them.

- When stretching those that lead, you need to provide a safety net so that the whole company or organization or company is not brought down if the person cannot rise to the challenge.

In my case, if I hadn’t written the paper or if it had not been accepted by the review committee, little harm would have been done to Robelle. Bob and Annabelle did take a reputational risk for their young company by having me, completely inexperienced as I was, get up on stage to represent the company. Fortunately, we did practice runs beforehand so that I was as prepared as I could be to do a good job.

In the end, it worked out for both Robelle and me. While I remember some stumbles and lots of “ahs” in that first presentation, I got through it. For the twenty years after that both Bob and I wrote a paper every year and traveled the planet presenting to technical and management audiences to create belief in our relatively small software company that people trusted their entire company to.

It all started with Bob and Annabelle issuing a challenge and taking a risk on what I could do.